Managers of a large food condiments manufacturer bragged that their finished products Inventory Record Accuracy (IRA) was 99%. They added that they met this level constantly, not just when I as a consultant was there auditing the manufacturer’s supply chain operations.

How do you compute the IRA? I asked the warehouse manager.

The warehouse office staff every morning printed the inventory records of every product item or stock-keeping unit (SKU), the manager replied. A team would then go out to the warehouse and count the SKUs and match them with the records.

If the staff catches a discrepancy, then they’d quickly either seek the missing item or check why there’s more on storage than in record. Most of the time they’d find the cause of the error and correct it. Thus, within an hour, the team would edit the inventory records to match what are in storage. Any unresolved discrepancy would be investigated, and this often did not exceed one percent (1%) from the IRA.

Inventory Record Accuracy (IRA) measures the difference between inventory records and what are actually on hand at any instant of time. Simply put, if a record matches what’s counted, it’s accurate. If it doesn’t, it’s not.

Is the food condiments manufacturer’s IRA really 99% as executives say it is? If the warehouse team is chronically making corrections, then probably not. IRA measures the matching of records versus counted items the first time around, and not after several iterations of corrections and editing.

Some may say it is unfair to measure IRA the first time around as reporting the figure doesn’t give one a chance to reconcile and correct any mistake. Some may feel IRA benefits the finance & accounting departments more than it does operations management. Hence, they would argue in favour of reconciliation & correction before reporting IRA.

IRA does benefit operations managers, I say, even more so than the finance & account department. If records don’t match what’s there on the floor, then operations managers won’t be getting a not-so-accurate picture of the inventories of items. Honest mistake or not, if there was any mismatch between records and actual count the first time, it’s highly likely that mismatch has been there since the last count, or for a significant time in between counts.

And when IRA is not-so-accurate, there will be risks & effects to the business:

- Items thought to be available for sale, aren’t.

- Order fulfilment teams might be invoicing items that are not there.

- Warehouse operators might not find items where they’re supposed to be;

- Or, they might find items in places where they are not supposed to be.

- Purchasers might order items that are not needed because they’re already there.

- Or, they might not order items they thought that are there but are not.

- Operations managers might not be aware of items on stock and are closer to expiring beyond their shelf lives.

- Accountants would not be reporting the right inventories and their corresponding values, which may result in errors to financial reports.

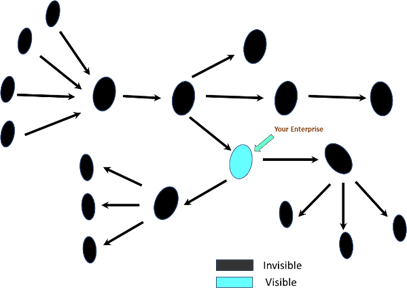

IRA amplifies the obvious deficiencies in an enterprise’s management of inventories. It, for example, bolsters the complaints of customers as to why they receive the wrong product. Or, for instance, how come storeroom staff can’t find an important spare part despite their computer saying it’s there, which results in costly delays to maintenance or repairs of vital equipment.

IRA helps supply chain managers trace and fix systematic mistakes such as wrong encoding of information, wrong counting, putting away items in the wrong place, and wrong products picked & shipped. IRA pinpoints which items need improvement in inventory management, be it finished product, work-in-process, part, component, packaging material, or ingredient. It provides the visibility for which items managers need to immediately focus on.

For items that are discrete or countable, One measures IRA by hit-and-miss. If records of 90 out of a 100 items match with what are actually counted, then the IRA is 90%. If there’s a match, it’s a hit in favour. If it’s a mismatch, it’s a miss, no matter how much the difference between the count and the record.

For non-discrete items, or items that are measured via continuous variables like weight, liquid volume, and pressure, one measures IRA against predetermined tolerances. For example, it’s a match if a storage inspection show 1,999.95 litres of coconut oil versus 2,000 litres of the same oil on record, given a tolerance of +/- 0.5 litre.

Technical professionals calculate tolerances from the properties of non-discrete items, such as for example, moisture content and temperature expansion. Managers would approve tolerances from the science of these items.

IRA also allows supply chain managers to check any item’s actual condition or characteristics versus specifications. If, for example, if every case of toothpaste counted is supposed to contain thirty-six (36) 100ml regular formula tubes, then whoever is taking inventory should ensure that this is so when they count the product’s cases on floor. It’s an automatic miss if the counter notices any characteristic not matching an item’s specification.

Operations managers should regularly update their products’ item code records. An item code record is a detailed profile of an item. It includes, but not limited to, an identification code, item’s specifications, unit of measures at different supply chain stages, its components or substances, its functional relation to a manufacturing process, its standard cost or price, its source (e.g., vendor or supplier), and its risk & safety information.

An item counted on floor must match the data of its item code. Any mismatch, no matter how seemingly mundane, is an automatic miss. It’s important enterprise managers regularly update their item code records as they identify the merchandise of the business.

Items which the enterprise buys, uses, or sells are not subject to one department or manager. Operations, finance, marketing, technical research & development, and even legal & administrative departments own the item records of an enterprise. Some companies assign the leadership of administering item codes to either the finance, marketing, R&D, and supply chain departments. Everyone, however, owns the item codes and the key to their effective management is the system & procedures that the enterprise sets up and enrols everyone into.

IRA reflects how effective the administration of item codes is. As it tells how well records match what’s on floor, it indicates how familiar operations managers are in the items they oversee from purchase, manufacture, to delivery.

Inventory Record Accuracy measures the match of what and how much items are on-hand versus what and how much merchandise are documented and deduced from transactions. It’s a comparison of what are in stock versus what are read in inventory databases.

IRA is not meant to be a performance measure which solely benefits the financial executives. It is a measure that helps supply chain managers correct and avoid errors in transactions and ensure value-added manufacturing & logistics activities are done right productively.

IRA lays out via transparency where supply chain professionals are performing not only in managing inventories but also in how effective and efficient they are in their day-to-day transactions.

It helps identify where problems lie in supply chains. And by identifying problems, supply chain engineers have the groundwork to improve the systems & structures underlying supply chain operations.